Graph all the things

analyzing all the things you forgot to wonder about

Traffic

2015-01-10

interests: traffic (skim for the results), PDEs

If you have learned to drive, your instructor may have told you to obey the "2-second rule", which states that you should drive such that your car is always 2 seconds behind the car ahead of you. It turns out that if everyone were obey this exactly, traffic jams would rarely ever disappear. Fortunately, there is a solution: if everyone adjusts their time to the next car based on their speed as in the following chart, traffic jams will dissipate more quickly. More modern suggestions for these times made from a safety standpoint match up closely.

| Speed/(km/hr) | Speed/mph | Time to next car/seconds |

| 0-30 | 0-19 | 1 |

| 31-62 | 20-39 | 2 |

| 63-100 | 40-63 | 3 |

| 101-143 | 64-90 | 4 |

The only discrepancy is that you may want to stay 2 seconds away even at very low speed. Please don't do anything stupid just because of this post.

Gamma

If you follow some sort of "-second rule" exactly, your distance to the next car is proportional to your speed. This rule makes sense if you are expecting to slow down, say, 20 km/hr if something unexpected happens, but the distance required to stop your car entirely is proportional to the square of your speed instead. For practical purposes, you might pick some rule where your distance to the next car is

I'm going to analyze some partial differential equations (PDEs) here, so if you aren't comfortable, feel free to skip to the plots - just make sure you understand that determines how you scale your distance to the next car with speed.

0 or 1 cases

0 or 1 cases

For simplicity, let's make the following assumptions:

Everyone obeys for some constant

and some

. For most of this post, I'll assume everyone uses the same

.

The road is infinitely long.

Everyone's speed is high enough that a car length is small compared to their distance to the next car (that means I'm only considering traffic jams where people slow down, not stop).

As with most traffic setups, the flux of cars through a particular section of road is

Here, the green dots represent particular cars as they move with the traffic. The shape of the traffic density is entirely determined by the initial condition of the road - it could be any other function, but it (and the cars) would still move in unison. However, this ubiquitous velocity could vary with time, so the problem has many possible solutions; it is not well-posed. We could observe all the cars speeding up or slowing down, as long as it was done in unison.

Since I just dealt with the case , I'm going to assume

for the rest of this post. These cases are more complicated, so until the end of the post I will also assume that each driver uses the same constant

. We know that

is inversely proportional to the traffic density

, so

General  case

case

In the case that is arbitrary but

is constant, our equations give

, which in turn means that the flux is

Solving this PDE is difficult since discontinuities appear when fast traffic and slow traffic meet, causing a shockwave. Here's an example of a shockwave forming with :

There is of course a physically acceptable solution after this discontinuity occurs - one in which the number of cars is conserved (the entropy condition). The discontinuity remains, moving at speed

where is the traffic density on the right of the shockwave and

is the density on the left. In the example above, that speed is

, which is somewhere between the speed of the fast traffic density and the slow traffic density. As alluded to before, the shock will move backward in the case that

. This actually happens in real life when cars stop within the jam (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7wm-pZp_mi0). Here's an animation:

This may appear to be the mirror image of the , case, but they are algebraically different. An algebraically similar situation actually arises when slow traffic follows fast traffic. This results in a sort of anti-shock where slow cars need to accelerate to fill in the growing gap between them and the fast cars, as seen in the next animation.

Fortunately, traffic jams ultimately dissipate as long as is not 0 or 1. While the jam is extending on one end, it is growing shorter on the other end at a faster rate. Here's an example with

:

What would be the ideal for eliminating traffic jams? For which

does the low traffic density "catch up" to the front of the traffic jam most quickly? You might have expected the answer: the smallest

possible. Unfortunately, this is a horrible idea unless you enjoy rear-ending everyone on the highway. If we only seriously consider

, the question gets interesting.

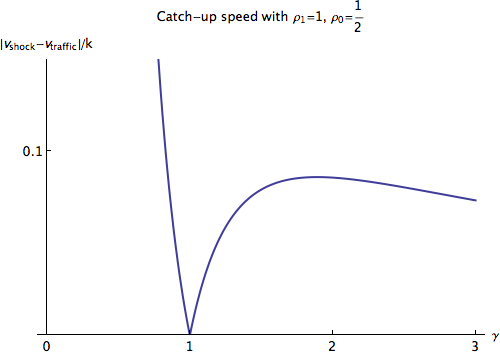

Remarkably, the best safe is always between 1 and 2. Take a look at this example where the traffic density in the jam is twice as high as normal:

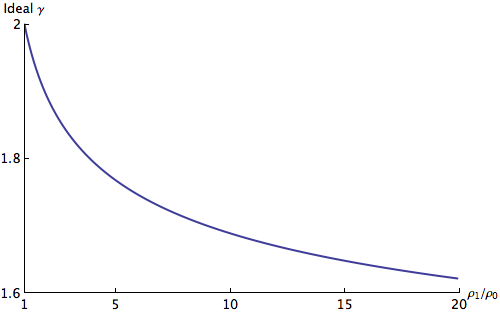

The denser the jam relative to the rest of the traffic, the lower should be. I'd say we can reasonably expect the density ratio

to be no more than 20, and in those cases, the best

is actually between 1.6 and 2. The catch-up speed is a fairly flat function of

in that interval anyway, so any

in that range will do. If you want to be picky, here's the optimal

as a function of

:

In general, I think is reasonable. That's what I used to make the chart at the top, along with the 3-second rule at 80 km/hr.

Here's the caveat: for , a short traffic jam slows down each driver less than a long section of slightly increased traffic. So why would we even want to dissipate traffic jams? The answer is the speed limit. If we enforce a speed limit, no matter how sparse the traffic becomes, no one will exceed a certain speed; if traffic is only slightly increased in one region, no one would have to slow down at all. This tends to be the case in reality, so long sections of slightly denser traffic usually cause little impedance.

More things to explore

If differs from car to car, then

does as well, and it propagates at the same speed as the cars. That implies

This is an abominable system of nonlinear partial differential equations. I plan on making a numerical method for this and animating some scenarios in a future post.

I also didn't have space to animate the effect of a speed limit on traffic, so I'll include that as well.